THE GIFTS AND GRACES OF MARRIAGE

Archbishop Anthony Fisher

An excerpt from the address of Most Rev Anthony Fisher OP – Ray Reid Memorial Lecture, Faith in Marriage Conference hosted by CatholicCare Social Services Parramatta and Australian Catholic University, Our Lady of Mercy College, Parramatta, Sunday 15 September 2013

1. What is marriage?

When Catholics talk about ‘the vocations crisis’ they are usually bemoaning the numbers who’ve left the priesthood and religious life and the shortage of newcomers thereto. Yet the more serious vocations crisis is in marriage. Far fewer people get married at all today and, of those who do, a far smaller proportion stay married than stay priests or religious. The marital breakdown rate in the West is now so high that some wonder if many moderns are simply unmarriageable: not because of any constitutional inadequacy but because they are conditioned to think of marriage as conditional, as a state that lasts ‘for as long as it works’. The ‘Get Out of Jail Free’ card of divorce is now so deeply ingrained in us that it is hard for people today to engage in the sort of total self-gift that marriage requires and that was taken for granted in previous societies. In the meantime, years of ‘living together’ and other experiences have habituated would-be spouses in a debilitating non-commitment, so that even if they marry with high hopes, they have made themselves unlikely to sustain it.

It is not that people today are selfish, precisely, though many no doubt are. Rather it is that in our culture nothing is for keeps any more, whether that is relationships, work, housing, appliances, bodies, causes or morals. All is transient, revisable, renegotiable. As Pope Benedict XVI pointed out, our relativist culture that prioritises autonomy and pursuit of personal whim over all other values renders relationships terminable at will (e.g. Address to the Roman Rota, 26 January 2013). So, people already disinclined to self-sacrifice are unlikely to embrace it as a lifelong plan.

Paradoxically, then, our culture perpetuates the romantic idyll of ‘the perfect couple’ while discouraging the kind of compromise of self-will and foreclosure of other options that lasting relationships require.

If marriage, priesthood and consecrated life are to have a future, we must recover the ability to commit – for life, heart and soul – and so to persevere even when the going gets tough and the warm feelings go missing.

We must rediscover what it means “to love, honour and obey till death do us part”. Put baldly: we must recover the ability to marry.

Most civilisations, religions and philosophies have, at least until recently, understood marriage as the union of a man and woman, to the exclusion of all others, voluntarily entered into for life, whereby they undertake to live sexually and otherwise as husband and wife, all with a view to family. Despite cultural variations, family has consistently meant the community that results from marriage, that is, two or more generations related by blood, law and affections who share a domestic life. Marriage has been honoured as something good in itself, as well as good for spouses, children, church and community. Most people find their happiness in marriage and the marriage-based family, making it the goal of many of their day-to-day choices and the structuring principle of their identity and life narrative. Most people are reared in a marriage-based family. And both Church and community rely upon marriage-based families as the primordial cell of society and ‘the domestic church’.

In addition to the sort of philosophical and theological reflection upon which I rely in this paper, there is, in fact, a huge weight of psychological and sociological evidence of the importance of marriage and the marriage-based family. Married people are generally happier than their single, divorced, cohabiting or same-sex counterparts; they live longer and healthier lives; they have lower rates of depression, suicide and other mental health issues; they are more socially productive and less alienated from their work; and they do better on average across a range of physical, emotional and spiritual measures. Children brought up in families, in which their parents are dedicated to each other and to them for the long haul, also fare better across a range of social and psychological indices. Despite all sorts of academic ducking and weaving, the overwhelming weight of evidence is that pseudo-marriages, such as de facto, trial and same-sex ‘marriages’, do not yield the same benefits.

2. Anti-marriage revolution(s)

Yet our marital culture has been the subject of unremitting assaults over the past half-century. These have left us more muddled than any society in history about the meaning of marriage, more ambivalent than any about the desirability of marriage, and less able than any before us to sustain marriages and marriage-based families over the long haul.

Stage 1 was the sex-on-demand revolution of the 1960s in which the hippy generation denied that sex had a marital significance or any intrinsic limits. Every civilisation before this one had understood that marriage is the appropriate context for sexual relating, even if some individuals failed to observe this wisdom.

From the 1960s onwards, however, the growing acceptance of sex outside of marriage supported by contraception and abortion, allowed the West to sustain a copulation explosion at the same time as a population implosion.

This denied even Christians the traditional boundary notions that ‘sex is for marriage’ and ‘marriage is for family’.

Stage 2 was the divorce-on-demand revolution of the 1970s in which the me-generation cast to the wind the notion of lifelong commitments and the attendant self-sacrifice, except as a sentimental ideal for newlyweds and religious fanatics. From the 1970s the divorce rate in Western countries spiralled, robbing spouses and children of the experience of permanence and even Christians of the ‘for life’ horizon for marriage and family.

Stage 3 was the children-on-demand revolution of the 1980s in which the greed-is-good generation reconceived children as consumer goods for the shopper who has everything. Building on the contraceptive-abortion mentality of the previous two decades, children could now be manufactured in laboratories and quality-tested before birth and those with undesirable characteristics disposed of. No longer need there be any connection between children and marriage, or even between children and ‘marital’ acts. Both fertility and infertility technologies were now used not merely to space children but also to prevent them altogether for a new generation of dual-income-no-kid DINKs and to provide children to single people, same-sex couples and others without sex.

Paul VI’s prophesy in Humanæ Vitæ of a radical break between love-making and life-making, sex and children, was fulfilled and even Christians were denied a sense of the mystery and givenness of fertility and children.

Stage 4 was the marriage-on-demand revolution of the 1990s in which the rave generation reconceived of weddings as another consumer experience. By the ’90s what was previously called ‘living in sin’ and having ‘illegitimate’ children (or worse names) came to be recognised as ‘de facto’ marriage and treated in law and society as the equal of marriage in all respects. Long-extended cohabitation or ‘trial marriage’ became normative; and marriage an optional extra especially for those who wanted the fairy-tale wedding experience. The current push for ‘same-sex marriage’ and the likely next push for polygamy follow the same pattern of treating various domestic arrangements as the equal in law and society of the marriage-based family, requiring only a promise to love sealed by sex.

Stage 5 is the sexuality-on-demand revolution of the 2000s. In post-modernity everything about us, including our sexuality and relationships, is negotiable. Human nature and natural institutions are no longer seen as fixed but rather matters of social convention or personal choice. A person might choose whether and when to be heterosexual, homosexual, transgender or whatever, for now; to change their sex anatomically and their gender preferentially; or to couple with one or more persons of any sex or gender contemporaneously or sequentially. Marriage itself becomes infinitely malleable and people must be free to marry as they wish, unbound by norms of sexual complementarity, openness to children, permanence or exclusivity. Family, likewise, is to be manufactured on demand by and for and with whomever people please. In this process the notions of sexuality and procreation, marriage and family are expanded to the point of triviality.

These five revolutions have together robbed even many Christians of a coherent understanding of the gift that marriage and family are and of the special support real marriages and marriage-based families deserve. Part of the evangelical task of the Church and especially of marriage educators and counsellors is to help people recover that understanding and provide that support so that people may not only appreciate the gift but derive the divine graces attendant upon its being lived well.

3. Marriage as sacrament

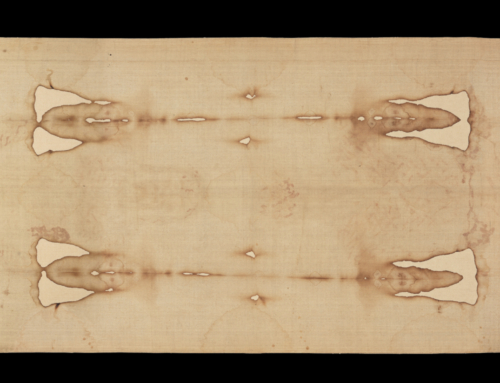

In Bosnia-Herzegovina there is a town called Siroki-Brijeg with a population of about 27,000 people which has never recorded a single divorce or broken family! (here)To Australian ears this may sound incredible, the result of bad record-keeping or draconian social control. How else could this occur in the 21stCentury? Well, the local inhabitants have an interesting custom. On their wedding day the bride and groom bring an object to Church to be blessed with them. They place their right hands upon it and the priest binds their hands to it with his stole as they pronounce their vows. Having been declared man and wife the newlyweds kiss the object before kissing each other. They then hang it in a place of honour in their new home.

It is, of course, a crucifix. After blessing it the priest proclaims to the spouses: “You have found your Cross! It is a Cross to love and carry with you, a Cross not to be discarded but cherished”.

Marriage, the thought seems to be, is a crucifixion. This is very much at odds with the Western romantic tradition with its classics such as the TV show Neighbours and the Hallmark Valentine’s Day card; this romantic tradition proposes a heart-shaped, touchy-feely sort of marital love, rather than the cross-shaped, self-sacrificial love of the Christian tradition. It is increasingly counter-cultural in communities like ours to consider marriage as family-focussed and God-focussed, rather than me-focussed, as a vocation rather than a lifestyle choice, as a mission given rather than fairy-tale pageant designed by a wedding planner and ‘bridezilla’.

The symbolism of the Siroki-Brijeg marriage crucifix is a powerful one and captures an aspect of marriage that we may be uncomfortable talking about but which I think is essential to face directly. The 16th Century Council of Trent famously defined the Catholic doctrine of justification. Christ’s sacrifice on the Cross, represented in the crucifix, is “the source of eternal salvation” by which “Jesus merited justification for us”. All Christians are called to participate in this according to their state and circumstances in life. Christ’s call to “take up our cross and follow” Him (Mt 16:24; cf. CCC 618; Vatican II,GS 22) is not for martyrs only, or for consecrated religious only, but for all the baptised. Now this same Council of Trent and the tradition that followed it confirmed that the marriage of two Christians is a true sacrament ordained by God, one that signifies the mystical marriage of Christ to His Church; that it is ordered to the good of the spouses and their offspring; that it vows a partnership of the whole of life which is not ended even by the heresy, absence or adultery by one’s spouse; that it therefore cannot be entered by those under a vow of celibacy or a previous marriage while the first spouse lives. Concubinage, polygamy, clandestine marriages and ‘remarriage’ after civil divorce without annulment were condemned in the decree Tametsi which a recent historian has observed was the Tridentine decree that most affected ordinary Catholics (John O’Malley, Trent: What Happened at the Council, p.226). The stage was set for the high, even romantic, theology of marriage that developed in subsequent centuries.

So Trent was both the Council of the Cross and the Council of Marriage and in my view this was no coincidence.

Though all the sacraments communicate the graces of the Paschal Mystery to us, the place where most of the faithful experience Christ’s Passion and its redemptive fruits in their own lives is in marriage. While consecrated religious make a solemn vow and the clergy receive a sacrament that ‘orders’ their lives, spouses both make a solemn vow and participate in a sacrament of vocation designed to make them holy.

4. Crucified joy

In the good old days bishops used to come around in advance of conferring the Sacrament of Confirmation and examine the young candidates. A story is told of one who asked a child, “What is matrimony?” In her nervousness she answered, “Matrimony is a place of trial where souls suffer for a time on account of their sins”. “Foolish girl,” the nun in charge intervened, “that’s purgatory not matrimony.” “Let her alone,” said the bishop, “what would we know about matrimony?”

Jokes aside, what the bishop realised was that love can be difficult sometimes, even for the best of couples. It requires sacrifice and purification.

True love is self-giving rather than self-serving, self-spending rather than self-willed, forgiving rather than grudging; it demands forbearance and perseverance and constant re-expression in acts of love; it loves even when loving is hard.

Here, too, is a place to reflect upon the growing reality of ‘broken’ marriages in our society. There are many whys and wherefores here, but it should not be presumed that every marital breakdown is due to a lack of good will on the part of one or both parties or that God has somehow abandoned these two people (and their children and extended families) to their fate. Even troubled marriages are a source of grace and if lived in the appropriate spirit the suffering endured may itself be part of the redemptive action of the sacrament. Here the mystery of the cross and resurrection is emotionally and spiritually opaque, especially for those undergoing marital ‘breakdown’, but we know by faith (if not by feeling) that where sin and suffering abound, grace abounds the more.

Not that sacramental marriage is supposed to be unrelieved misery! If it were, we could hardly call it a human gift and source of divine graces.

The sacramental notion of marriage, far from eschewing or demeaning the intimacy and personal fulfilment proper to spouses, purifies and raises that intimacy to communion and that fulfilment to blessedness. But it achieves much of that intimacy and fulfilment precisely in the fascinating but challenging complementarity of the sexes, in the commitment to hold fast through thick and thin, in the exclusivity and permanence that run contrary to human temptation, and above all in the readiness to enlarge that love by having a family. Whatever the physical and psychological consolations, marriage is intended as a path to holiness, and emotional and spiritual growth rarely comes without some experiences of pruning along the way.

So, when the Scriptures use the analogy of a marriage to describe God’s relationship with Israel or Christ’s relationship to His Church, it is not about lovey-dovey feelings so much as a concrete and determined choice, at least on God’s part, to love faithfully, no matter what, and in expectation of abundant fruitfulness if that love is returned. Certain aspects of the natural institution of marriage help us understand the relationship between God and the individual soul and Christ and the believing community. By ‘reciprocal illumination’ God’s relationship to us can help us understand what the marriage between human beings should be.

The gift of a genuine, consummated marriage between a baptised man and woman is a ‘sacramental’ covenant, both indissoluble and grace-giving (CCC1640). St Augustine identified three ends or purposes here: fides, the unitive dimension, for marriage joins two bodies, souls and lives in a lifelong partnership or love affair with the spouse; proles, the procreative dimension, for marital acts are potentially procreative and marriage thus the nursery for children and a love affair with another generation; and, for believers,sacramentum, the sanctifying dimension, because marriage makes the spouses holy and so serves the building up of the Kingdom, the love affair with God (De bono coniugii; cf. Vatican II, GS 48). The ‘one flesh’ union of themarital act thus concretises a comprehensive union of persons and lives (cf.Gen 2:24, Mt 19:5, Eph 5:31).

Natural marital love is an entry point to the mystery of agape, that self-donative love of Christ. Thus, at His Last Supper Christ washed the feet of His disciples: this is normally seen as a demonstration of His teaching about authority and service, which it no doubt was; but foot-washing was also a marital act in the ancient world and so Christ is washing the feet of His bride, the Church. Next He takes bread and says the blessing at His Last-Supper-become-Wedding-Reception and declares to His bride, “Here is my body given for you”. Finally, from His Cross-become-marital-bed He declares “Consummatum est – it is consummated”. As it is unthinkable that Christ would dissolve His union to the Church or refuse to make that union fruitful in new members, so it becomes unthinkable for Catholics to redefinemarriage in ways that deliberately exclude from the beginning or render inoperative thereafter permanence, fruitfulness, complementarity or sacramental grace.

So the mystery of marriage might be described as the mystery of crucified joy: the gift of a natural union so comprehensive that it unites persons in a self-giving love that expands their hearts and, God willing, gives them more to love, including children as the fruit of their union.

Good marriages have the crucifix at the centre not because of grin-and-bear-it stoicism but because this represents the source of redemption, fecundity and ultimate happiness. The horizontal gift of a human or earthly union is met by the vertical graces of a sacramental or heavenly union and that meeting of horizontal and vertical is the cross.

5. Ecclesial and social gift

I have said a little about the graces that flow to the spouses and children from the human gift of marriage; I want to conclude with a few thoughts on the graces that flow to Church and society. Stanford University researcher Mary Eberstadt has published a series of articles, some later enlarged as books, including “Home-Alone America”, “How the West Lost God”, “The Vindication of Humanæ vitæ” and “Christianity Lite”. Citing an enormous range of sociological research she has argued for a two-way causal relationship between marriage and family life on the one hand and Church and social life on the other. Many people have observed that if faith in God and country are strong, marriage and family will be well understood or supported, and people will be more likely to enter and to sustain marriages and to have larger families; but if faith in God and country are weak, marriage and family will suffer, Eberstadt observes that the vice versa is also true: if marriage and family are strong, religious observance and secular citizenship will also be strong; but if marriage and family are weak, then religious practice will decline and social problems multiply.

Declining religious and social support makes marriage and family less sustainable. As the last several popes have taught, it is only by accepting the Gospel that humanity’s aspirations for marriage and the family can be achieved; faith equips married people with a “plan bigger than our own ideas and undertakings” (e.g. Bld John Paul II, Familiaris consortio 3; Pope Francis, Lumen Fidei 52). But at least as important or more so, according to Eberstadt, is the reverse effect. If marriages and families decline in vibrancy, so will churches and communities. Married men are more likely to go to church or to care about politics than single men; spouses with children even more so. Not only are religious people likely to want or allow more children, but the more marriage and children people have, the more religious they become.

Something about living in families inclines people to being more religiously and socially concerned. Eberstadt thinks experiences such as courting, wedding, pregnancy, childbirth and early child rearing open people up to transcendence, to hope, to God. So Christians (and others) naturally use images of father and bridegroom for God. But what sense will this make to children (or adults) whose experience of marriage and paternity is non-existent or limited to a series of temporary partners and step-dads? How will the wonder of the Incarnation speak to adults unused to babies and perhaps fearful or hostile to the very idea? Weakened natural families and the increase in quasi-families that do not conform to traditional structures leave individuals not only less likely to find the Christian moral code convincing but also less able to access the grammar and meaning of the Christian story.

If Eberstadt’s thesis is true, this means that the vocational crisis in marriage is potentially lethal for the Christian religion. It will also have implications for the surrounding society.

Obviously it has demographic effects: many modern nations and cultures are projected to die as a result of the population not replacing themselves. It also affects people’s readiness to invest themselves in common projects or in a future beyond themselves. The atomisation of individuals plays out in all sorts of problematic ways in contemporary culture and society. As households get smaller, until they reduce to one, people get used to living and dying alone. Though we are made for human community and divine communion, we adopt a lifestyle that is self-contained, self-reliant, inward. The Book of Genesis tells us that it is not good for a man to be alone; modernity says the opposite. Sure, a series of transient relationships are OK, but don’t become too comfortable, too reliant, too comprehensive in your union. If marriage is the genesis of Church and society this anti-marriage ideology could spell the end of both.

For the sorts of reasons I’ve touched upon today, the Church is notoriously pro-marriage and pro-family. But some think her niggardly, even discriminatory, in not allowing it to everyone. Some activists, politicians and journalists are presently pushing hard for the legal recognition of same-sex ‘marriages’. For reasons I have outlined in the September 2013 issue of our diocesan magazine, Catholic Outlook, and elsewhere, this is a bad idea. Catholic resistance to changing the definition of marriage is not about homophobia, unjust discrimination or a failure to love same-sex attracted people: we all know and love homosexual people and if our Church has failed to be as supportive to them as we should that is a mistake which we should correct. But we will not help that situation by abandoning our love and support for real marriage and, therefore, for married people and the marriage-based family.

To read the full article, from the Marriage Resource Centre, please click here.