We’ve all been there: obsessing over a faux pas we committed at a party, infuriated by an unkind word from a colleague, ruminating over a tough break-up with a spouse or friend. We suffer some misfortune—big or small, real or imagined—and the pain or humiliation sticks with us for hours, days, or even years afterward.

We’ve all been there: obsessing over a faux pas we committed at a party, infuriated by an unkind word from a colleague, ruminating over a tough break-up with a spouse or friend. We suffer some misfortune—big or small, real or imagined—and the pain or humiliation sticks with us for hours, days, or even years afterward.

This article is an excerpt from the transcript of an interview of Rick Hanson.

By Michael Bergeisen.

September 22, 2010

Full article: here

Pod cast: here

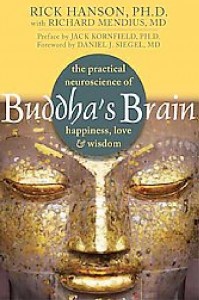

Best-selling author Rick Hanson explains how we can rewire our brains for lasting happiness—part of Greater Good’s podcast series.

“The mind is like Velcro for negative experiences,” psychologist Rick Hanson is fond of saying, “and Teflon for positive ones.”

But it doesn’t have to be this way. Drawing on some of the latest findings from neuroscience, Hanson has spent years exploring how we can overcome our brain’s natural “negativity bias” and learn to internalize positive experiences more deeply—while minimizing the harmful physical and psychological effects of dwelling on the negative.

For years, research has shown that, over time, our experiences literally reshape our brains and can change our nervous systems, for better or worse. Now, neuroscientists and psychologists like Hanson are zeroing in on how we can take advantage of this “plasticity” of the brain to cultivate and sustain positive emotions.

RH: The classic line in neural psychology is, “As neurons fire together they wire together.” The seemingly immaterial and ephemeral flow of the thoughts and feelings through your mind leaves behind traces in your brain. So the takeaway point is to be very thoughtful about what you think about all day long. A lot of us think about crud all day long. We’re worrying about this, we’re planning that, we’re obsessing over something bad that might happen that hasn’t even happened, whatever. Or we’re thinking about what a loser we are, how we just never get anywhere in life, or people don’t love us, or we get mistreated—and there’s a place for that if it’s productive.

But much of the time, we’re just running those movies in the mental simulator. The problem is, as we run those movies, they’re leaving behind traces of neural structure that are negativistic, depressive, pessimistic, and very self-critical.

MB: So we initially talked about the more positive aspects of the brain. Now you’ve started identifying parts of the brain that have a more negative slant. And in your book, you do talk about this negativity bias in our brains. Can you describe that a bit more?

RH: Our ancestors, the ones who lived to pass on their genes, got better and better and better at making a crucial decision many times a day about whether to approach something or avoid it. Approach the pleasant, avoid the unpleasant. Approach the carrot, duck the stick.

Alright, now the problem is that sticks are much more important to pay attention to in the wild than carrots because if you miss a carrot today, you’ll get another chance at one tomorrow, but if you don’t avoid a stick today—Wham!—you’re not gonna get a crack at a carrot tomorrow.

So we’ve developed what’s called in science a “negativity bias,” which means that the brain, to help us survive, preferentially looks for, reacts to, stores, and then recalls negative information over positive information. For example, there’s a pretty famous finding in the realm of relationship psychology from John Gottman, of the University of Washington, that it takes at least five positive interactions to make up for just one negative one. In other words, in effect, a negative interaction in an important relationship is five times more powerful than a positive interaction. That’s an example of the negativity bias at work.

So then the really interesting question becomes: How can you overcome it? That’s why, for me, taking in the good is an absolutely crucial skill to develop, and a wonderful way to balance this unfair tilt embedded in your own nervous system.