Dr Marshall Ballantine–Jones

Biography

Dr Marshall Ballantine–Jones, CEO of DigiHelp Publishing and Founder of Resist Ministries, specializes in research and education to schools and churches

focusing on both the impact from exposure to pornography and social media. Ordained as an Anglican minister, he holds a PhD from Sydney University, and is a sought–after speaker, writer, trainer, and consultant.

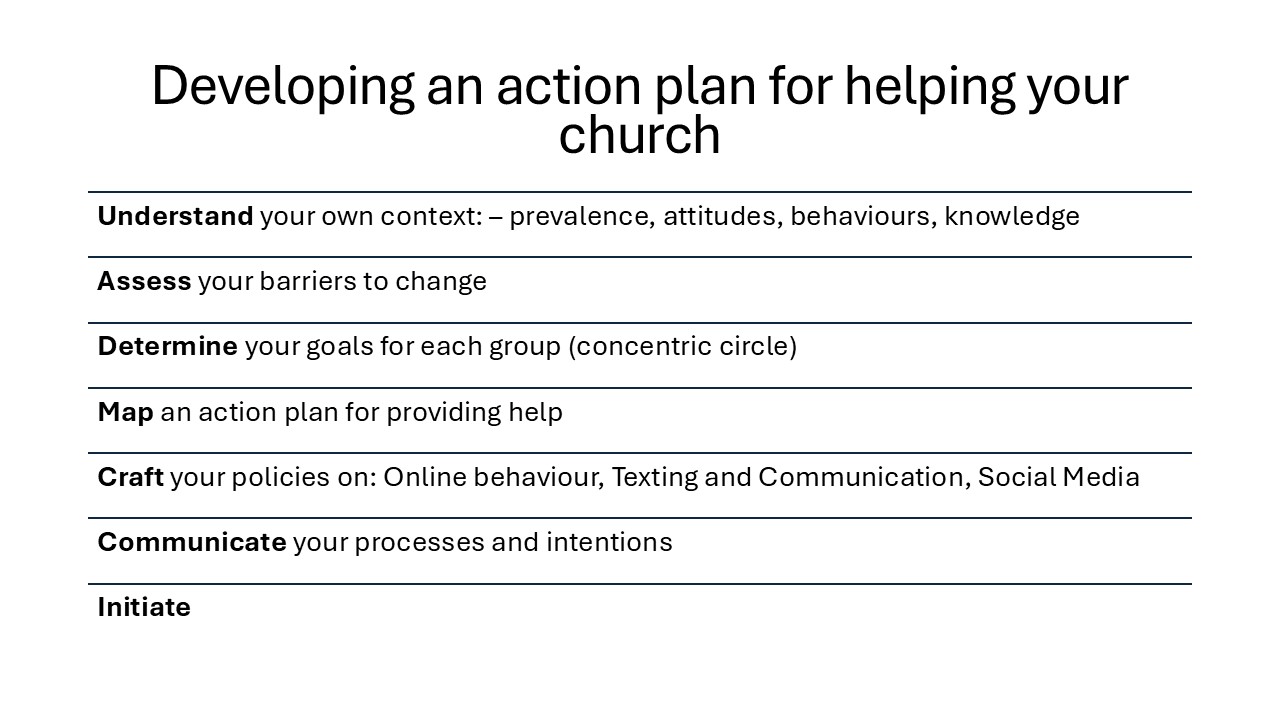

This session will tackle the challenges church denominations face in addressing pornography. Churches must first understand the realities their members experience. Then, they need to educate, equip, and mobilize leaders to effectively confront the issue. A strategic response is essential to provide meaningful support to members, families, and young people in both prevention and recovery. To establish healthy practices that benefit the long–term health of congregations and workplaces, senior leaders must commit time and resources to transform good intentions into lasting, systemic change.

Transcript

So, let’s briefly look at this, there are three things I want to talk about today. The first is that porn is a big problem in our churches, particularly amongst our leaders, so firstly here is just a little bit of data from America.

This was produced about the time we were doing our own study and in those years, 39% of practicing Christians are comfortable with their porn use. Nearly 60% of youth pastors and 40% of senior pastors use porn more than monthly. 75% of youth pastors and 64% of senior pastors say the porn has negatively impacted their ministry at some time.

That’s American data, but that was a very large sample size, well we studied our own people. We asked two questions 1. Is pornography a problem for you? and if it is a problem for you how much? Then we asked them 2. If this was a problem for you, who would you trust to talk about this with?

We sent the survey out to everyone who worked in the Anglican diocese. All 1200 workers which included not just senior clergy and lay leaders, but also to gardeners and secretaries and anyone who was on the payroll got the survey and the responses came back. What did we find?

Well, we found that 47% of rectors were viewing pornography monthly or more. Rector is your Parish priest and 61% of males under 40 viewed pornography monthly or more. 20% of females under 40 were viewing pornography monthly or more.

At the time there was already quite a large body of secular research on how much porn was impacting people in the community, not only in Australia and America, but Europe and across the world and this data said that what was going on in our people, our professional people, was no different really than the secular data. It’s a big issue, now you won’t know what officially your situation is under the hood with your workers, in either this diocese or anywhere else across our country, but it’s likely if they were a person who lived their adolescent years with access to the internet they’re going to be in this space here. Because that seems to be universal the 70, 20 ratio seems to pop up in many studies 70% of males and 20% of females will be looking at porn a lot. That’s in Christian circles interdenominationally as well as secular. Now depending on the survey and depending on the age group, those numbers move but that seems to be what we’ve seen.

So, we then asked who would you trust? This quickly exposed the “trust” dilemma, because most of them said that they would never trust a diocesan official but some of them would be comfortable to trust someone in a confidential and an anonymous situation, for example a therapist.

So, this immediately raised a challenge to the diocese because we know there’s a problem out there based on this confidential and this anonymous survey but at the same time we aren’t hearing this face to face. Why aren’t we hearing this?

Why aren’t they coming to us? The reality is because they feel deeply threatened by it. They feel professionally threatened by it. They don’t want to disclose this to someone in the system in case the repercussions are going to be serious. In the case of my tribe with the Anglicans, many of these people who go into vocational work have given up lucrative careers.

They dedicate themselves to years of study, they move their families from here to there, put them in the schools, there is a cost to stop that and so that’s one of the issues.

Another reason why we don’t get the problem. Our people in the system don’t appreciate the breadth of the problem, as it was in this anecdote that I told you, the head of the training at the time not only didn’t believe there was a problem because he hadn’t heard about it, and it wasn’t in his experience. But he didn’t want to believe it, because he wanted to have this ideal view of the institution. If the people who are in our roles of leadership have, I don’t know – the blinkers on, or just haven’t had the experience that younger generations have in this area, we could be missing a lot of this and just not discussing or addressing it properly. Of course, with this comes a broader issue (and certainly this was the case 10 years ago) – that we didn’t understand the nature of the problem enough. Certainly, how to address it – which is what we now have a lot more information on.

So some questions that we could ask at this point include: Are we asking the right questions of our clergy? Our lay leaders? As well as those who are coming through and inquiring about vocational work in the future?

Does the process that we put in place provoke dishonesty? So, for example again in the Anglican system, they have a questionnaire for all new ordained candidates, and the candidates are asked a series of questions as part of this questionnaire about their use of pornography. Their policy is that if they say “I’ve used pornography in the last 12 months”, that if “I’ve looked at it and used it” (for self-gratification purposes), they would end the process of ordination for 12 months until they can get a sign off from a therapist to say that they’ve been clean and free from it. That’s the standard now. In one sense it’s an important bar that they set. They have taken the view that we want to guarantee our people, that the clergy we’re given them, are people who are Godly and honourable have self-control. Which is noble but the problem is they’re only hearing from about 10-15% of their candidates that they’ve got a porn problem. But we know that anywhere up to 75% of them actually have a porn problem. So, they’re not being honest. Is there a better way that we can go about getting the help to those that need the help, while also having the duty of care to our people as an institution?

So, these are questions to be asked, and this takes a fair bit of wrestling with. What we also know in the research generally of sexuality (certainly when it comes to sensitive stuff related to vocational areas like pornography and clergy), is that when the questions are asked in a confidential way and in an anonymous way, we get a much clearer picture of the truth than if we are asking in a way where the answer is publicly known, or if there can be a repercussion to the answer.

So, I guess as a little bit of advice to people thinking about doing this deeper research in your environment, be aware that if you want to get the truth of the answer of how this is affecting your people. Put the questions in the most confidential and anonymous way possible. Otherwise, you won’t get a clear picture. Now the third area that I want to talk about is pastoral considerations because in the aftermath of this research the archbishop of the day received this and he saw that the problem of porn was big but unfortunately, we didn’t have a solution for it. Well, that’s been part of what my mission has been. To find the solutions. I actually focused my PhD on middle and senior high school students, and I did an extensive development of effective school curriculum that can reduce the negative effects of online sexualisation. That went well, but the church wanted to get some answers also, and there are some principles that we’ve learned, but the problem is that our institutions, that is our actual churches, aren’t ready to minister the solutions very easily.

One of the things that we found with our churches (and I did a study of about a dozen churches, not all Anglican by the way, just churches I had access to), and asked them the question “are you ready to help someone if they come to you?” We worked out that most churches weren’t ready, even the churches that were rolling out courses and programs on the side to help problematic pornographic behaviours. Here are some of the reasons why. Churches don’t understand the problem. Often that is the nature of the problem as it presents in the pornified person. Including whether they at the full-blown addiction end or have compulsive behaviours, as well as in the cases we’ve heard today – people who are affected by those living with a porn problem, to support those in trauma. Leaders lack the skills and the interest, as well as the resources to roll out a support program, or solution for the person who comes to them.

We still find in the church that judgmentalism is a very potent dissuader of coming forward. Not just that they feel shame and guilt, which is certainly part of it but also that when they do come forward they’ll feel like they’ll be hit with the moral stick and that they won’t get that type of gracious welcome that they’re desperate for (as they try and take those tentative steps forward).

A lot of people just don’t come forward to get help because they have tried in the past and what has been done in the past didn’t work, so they’ve given up hope. After somebody gets help that’s not the end of the journey. For many people with a problematic behaviour like sex addiction – that’s a lifelong struggle and we need to have some sufficient resources to keep them going into the long run.

So, there are some barriers to change, and we found that with these barriers to change, churches can then have an internal discussion among their own leaders and decision makers and strategists about how we can actually deploy some effective solutions.

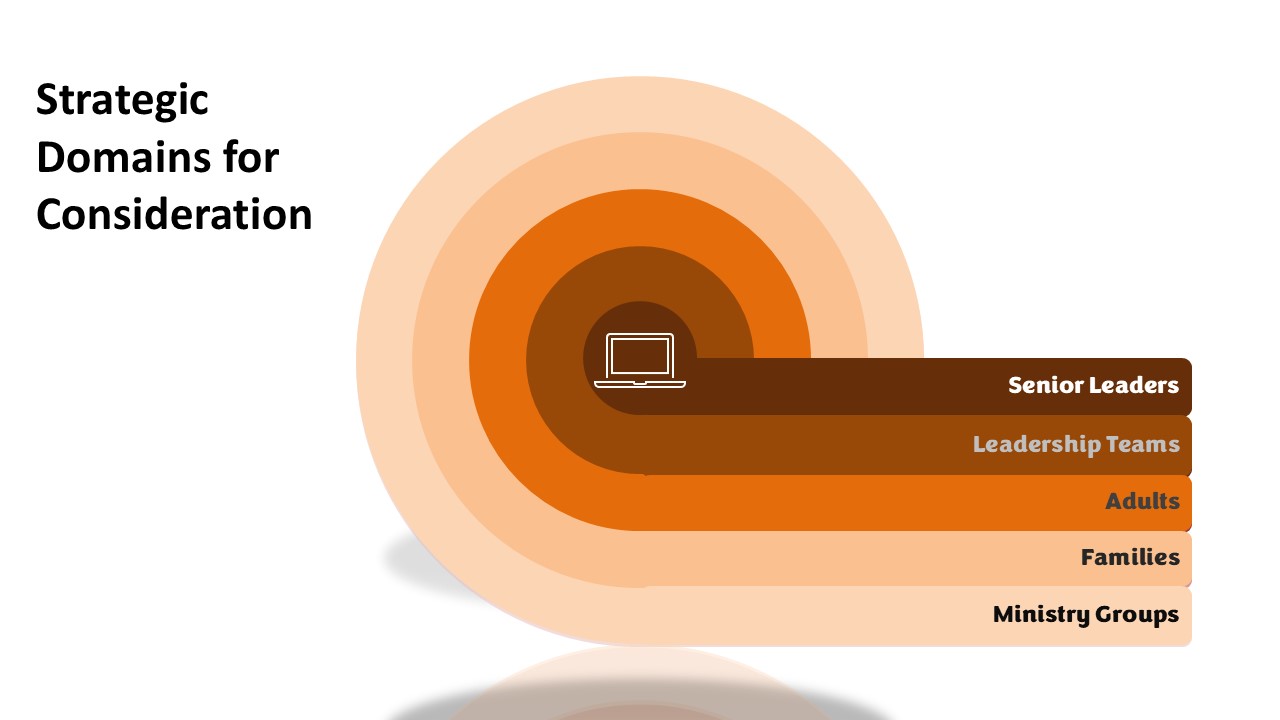

I want to suggest for anyone in a parish context that if you’re dealing with people coming in your churches to get help, well here are some arenas that you can look at. Obviously, the senior leaders themselves need to have a strategy, that strategy is how they will protect themselves, how they’ll deal with a current negative behaviour, or how they will act to maintain and preserve good integrity. They need to have policies about their teams, of what are the standards, not only of acceptable behaviour, but how they deal with those in both training, as well as remedial attention and so forth. Then we’ve got those in the spheres of our congregation the adults and whatever the subgroups are within the church. Families, and particularly parents and children, strategising for them, as well as special interest groups including youth and children, men’s and women’s ministries, and so forth. So, there are some practical ways that you can address that and in terms of our clergy themselves. I wish we had more time to talk about this and I’m very happy to talk later with other people, but we do know that there are effective solutions right now that can be deployed to lead people to change.

We asked this at the end of the last discussion and the evidence is clear that with hard work, people can move forward into a state of reliable trustworthy change, that is manageable lifelong. Part of that involves what we now know as neuroplastic change, because we know that with the sheer exposure to super normal stimuli – the brain changes. But it can change back with work and there’s a process there and those who are in the psychotherapeutic professions here, it’s really helpful for you guys to get familiar with the latest research on this and add this to your arsenal of support to people. Because this is a very important part of people’s necessary change. We know that abstinence is key, but we know that nothing’s going to change for the person unless they want it – that it’s not just a desire for the good, but it’s also a remorse for escaping the wrong. Some shame is important, because we know we’re engaging in wrong behaviour, sorrowful shame leads to repentance and when we’re talking about people of faith coming to the Cross of Christ and having our sins forgiven, that is the most liberating moment they’ll ever have. That’s where we need to bring them to. But they need to want that. And lastly, we’ve talked about this so much today and the research is clear – change happens best when it’s in the context of community. This is why groups are important.

We want support groups for our leaders, and support groups for our people. So again, how would this work in real time with clergy and churches who aren’t going to meet in a group comfortably of their parishioners? They need peer-on-peer type encouragement and that’s something where the central bodies can help facilitate in a way which is both safe and anonymous, but also effective. I would just want to put out, before I finish, that not everyone has a simple behavioural addiction, most people have a complex backstory and so everyone’s different. Everyone’s story is different and it’s vital that we understand that and that’s where we encourage everyone who’s got a problem behaviour to spend some time with a therapist, to get some self-awareness and to understand how to deal with those broader and more deep issues that relate.

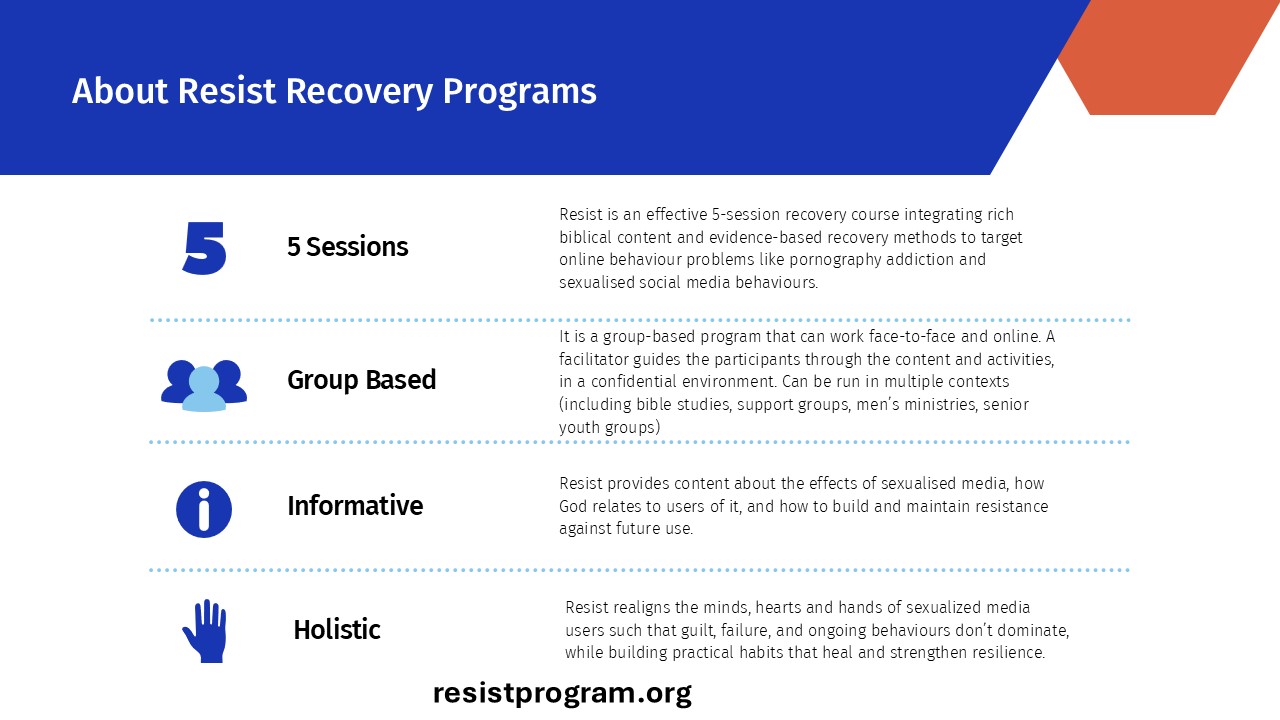

It’s important to know there are lots of choices you can use. For example, I’ve written a recovery program – it’s 5 weeks only and its low cost for churches at an entry level to get people on the effective pathway of change. We have reviewed this and it’s very effective and it would be a compliment to some other solutions.

If anyone here works in the school arena, I write school programs at the PDHPE level on online sexualized behaviour and so would be happy to talk about that with people in this room. Thank you for your time.

Three main points from this talk:

Prevalence and Impact of Pornography: Dr. Ballantine-Jones highlighted that pornography is a significant issue within church communities, especially among leaders. His research revealed that a substantial percentage of clergy, including youth pastors and rectors, regularly consume pornography, often reporting negative impacts on their ministry. This reflects broader societal trends and indicates a need for churches to confront this reality openly.

Challenges in Addressing the Issue: The talk discussed the barriers preventing effective communication about pornography within church structures. Many clergy feel threatened by the stigma associated with admitting to problematic use, leading to a culture of silence. Furthermore, traditional questionnaires and screening processes often discourage honesty due to fear of repercussions, thereby obscuring the true extent of the issue.

Need for Strategic Responses and Support: Dr. Ballantine-Jones emphasized the importance of creating supportive environments for individuals seeking help. He advocated for anonymous and confidential approaches to discussing pornography, as well as the development of educational programs and support groups within churches. This strategic response is crucial for fostering a culture of healing and accountability, enabling both clergy and congregants to seek help without fear of judgment.

Overall, the talk underscored the urgency for church leaders to understand and address the complex realities of pornography in their communities through education, support, and systemic change.