Shawn Van der Linden

Biography

Shawn is the Managing Director of Altum Integrated Pty Ltd, an Australian consultancy that partners with Catholic and faith-based organisations to integrate mission, mental health, and organisational wellbeing. An Accredited Mental Health Social Worker with qualifications in theology, social work, family therapy, and management, Shawn has over 30 years of experience across clinical and executive leadership roles, including senior appointments in Archdiocesan pastoral leadership, community services, Catholic education, and corporate psychology. Shawn serves as International Programs Director for the CatholicPsych Institute, offering Integrated Daily Dialogic Mentorship (IDDM) and supporting individuals in Australia and internationally. Through Altum Integrated, he leads consultancy projects focused on reviewing and renewing mental health and wellbeing systems, leadership, and organisational culture, while also maintaining a private practice in psychotherapy, coaching, and clinical supervision. His work unites faith and psychology to help individuals, teams, and institutions flourish in mission, culture, and care.

The draw of pornography and the cycle of addiction are intricately linked to the human experience of shame. At its core, shame emerges from relational conflict and disconnection. True healing, therefore, requires more than merely stopping harmful behaviors; it demands a profound, transformative connection with others—one that liberates us from the burden of internalized shame. In this talk, I’ll propose that our Church must develop a new dimension of relational accompaniment to address this need.

Transcript

Today, I want to discuss transforming shame, an essential yet challenging emotion for us to understand and engage with. I believe that cultivating an awareness of shame is foundational, providing us with a way to navigate this powerful emotion.

To illustrate this, I’d like to introduce ‘Sarah’ as a composite case study. This example is drawn from my experience of walking with a number of clients over time, and the details have been intentionally blended and generalised. There is nothing here that identifies any individual person.

Sarah is a 29-year-old Catholic woman who is genuinely striving to live out her faith. She is highly educated, works in the health industry, and is connected to the Church in various ways. Despite her efforts, she sought help while trapped in destructive cycles of sexual addiction—engaging in multiple hookups, enduring deeply harmful relationships, and unraveling on many levels. Sarah requires a range of support, but central to her true healing, beyond the interventions she will need, is the transformation of her shame—specifically, the deep, internalized toxic shame that she carries.

It’s essential for us to engage with the nature of shame and to connect with it as best we can. Shame is a complex and often misunderstood emotion. It can be elusive, and when left unaddressed, it has a way of becoming internalized.

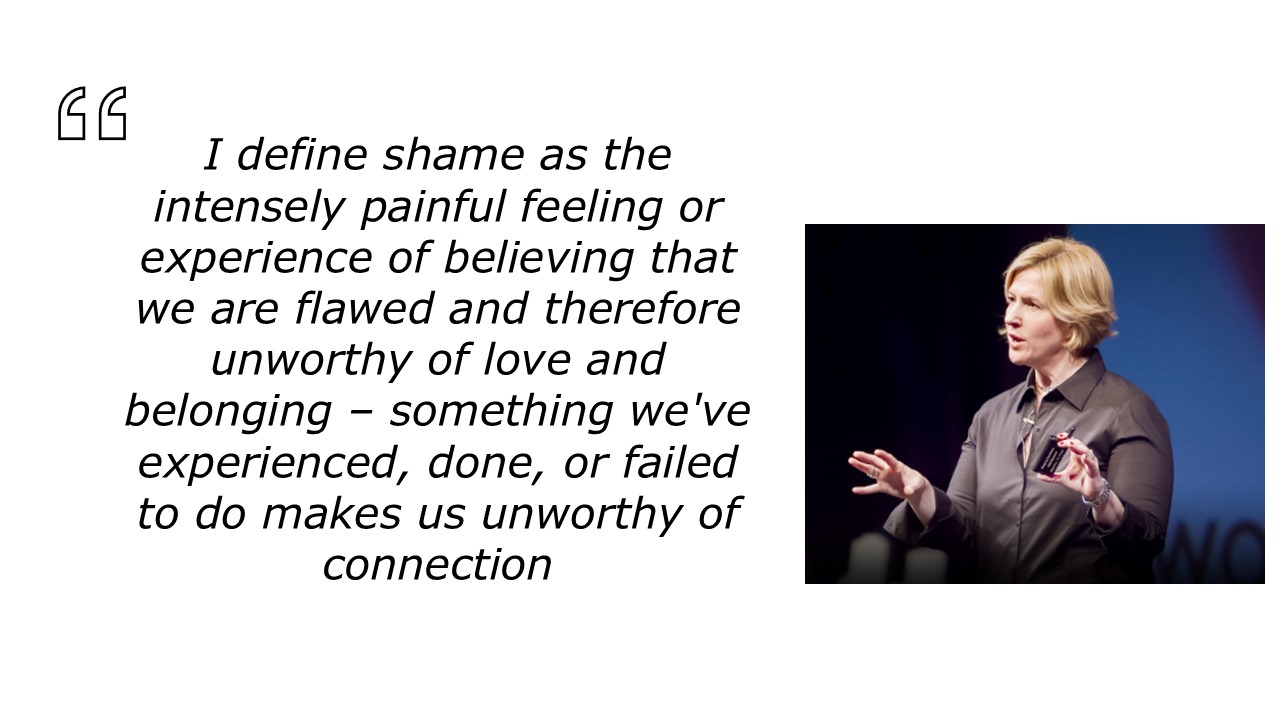

Shame can be profoundly distressing. Many of you may be familiar with Brene Brown’s work on this topic. Unlike guilt, shame is all-encompassing, often leading us to believe we are fundamentally inadequate. These deep-seated convictions can appear unexpectedly, and when we’re working with or supporting others, this sudden sense of overwhelm can catch them off guard.

In my experience, people often describe feeling shame in phrases like, “My heart sank into my stomach,” or “I don’t know why I suddenly felt so upset and overwhelmed.” Their reactions seem disproportionate to the situation, revealing that something deeper is at play.

These reactions signal deep internalized shame.

A critical first step, even briefly in our limited time, is to recognize shame as a primary emotion and to place it in context—particularly within an evolutionary framework. This understanding can provide us with situational awareness when we’re working with or supporting people as they navigate the experience of shame.

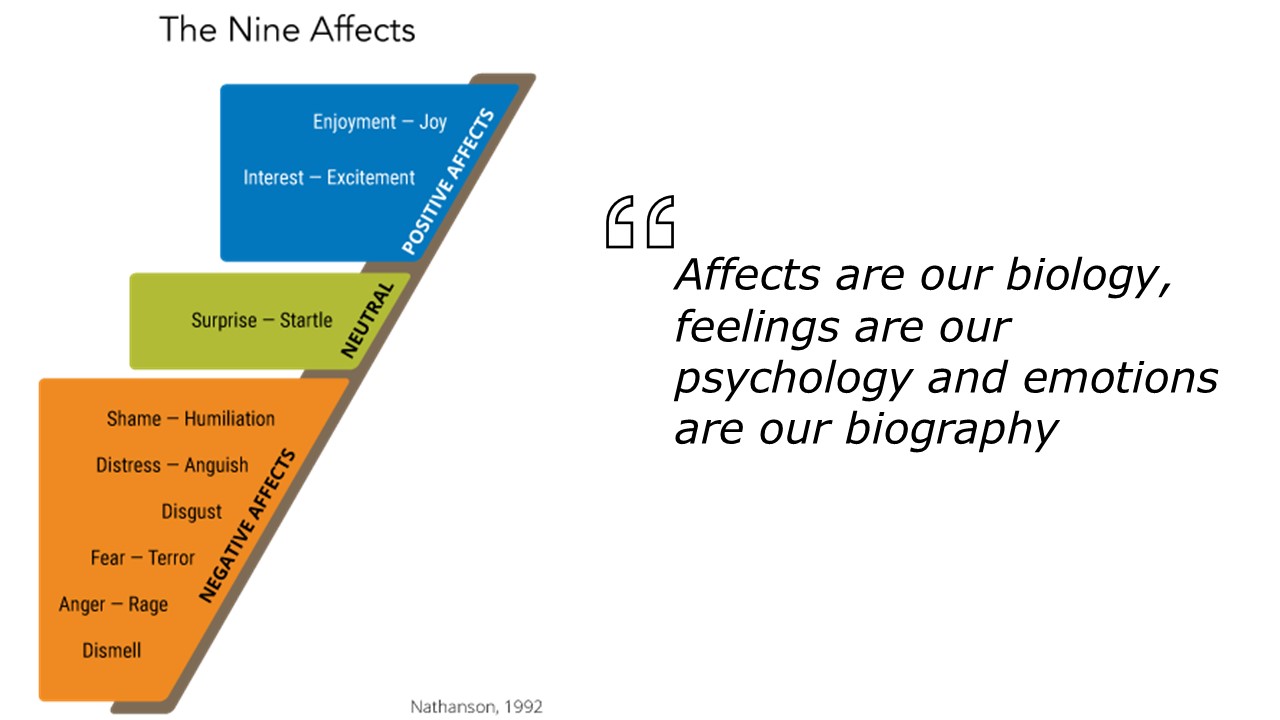

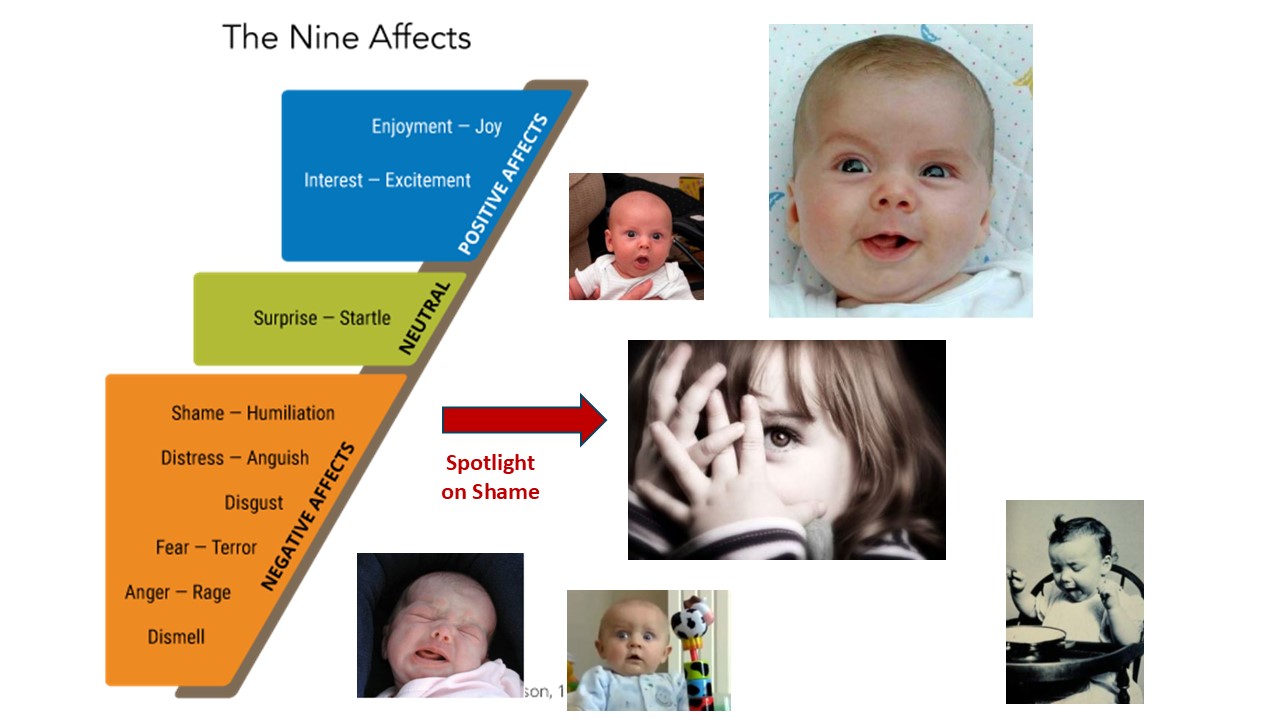

Silvan Tomkins, in his Affect Theory, identifies nine fundamental affects that are universal across cultures and ages. We all experience these affects—some positive, some neutral, and some negative.

An affect is essentially an innate biological response to neural stimuli. It connects us to the world around us, reflecting how our body interprets what’s happening in our environment. These affects act like alarm bells, signaling experiences as rewarding, punishing, or neutral. When we recognize these signals, they become our feelings, and when we relate these feelings to our personal history—our trauma, life experiences, and memories—they become part of our biography.

In this context, we experience a variety of affects, but the one we’re focusing on here is the shame and humiliation affect. This affect serves as a powerful, built-in self-protection signal.

Shame alerts us that something has disrupted our sense of belonging, joy, or excitement. This signal is especially strong in our interpersonal relationships, impacting our sense of belonging and acceptance within a group. Shame, then, is fundamentally tied to our social connections.

The impact of shame is profound; it is often described as the most stressful of human emotions. It can trigger a freeze response, activating the brain’s survival center and releasing cortisol at higher levels than many other emotions, including fear and anger.

Shame is a powerful response, one often felt as a deeply visceral experience, connected to what we might call the “heart-brain.” This connection may explain why we talk about having a “broken heart”—it’s a metaphor for the intense experience that shame can bring.

It may be surprising, but shame can be reframed. Instead of viewing shame solely as a villain, we can recognize it as a signal—perhaps even a hero—if we understand its role correctly.

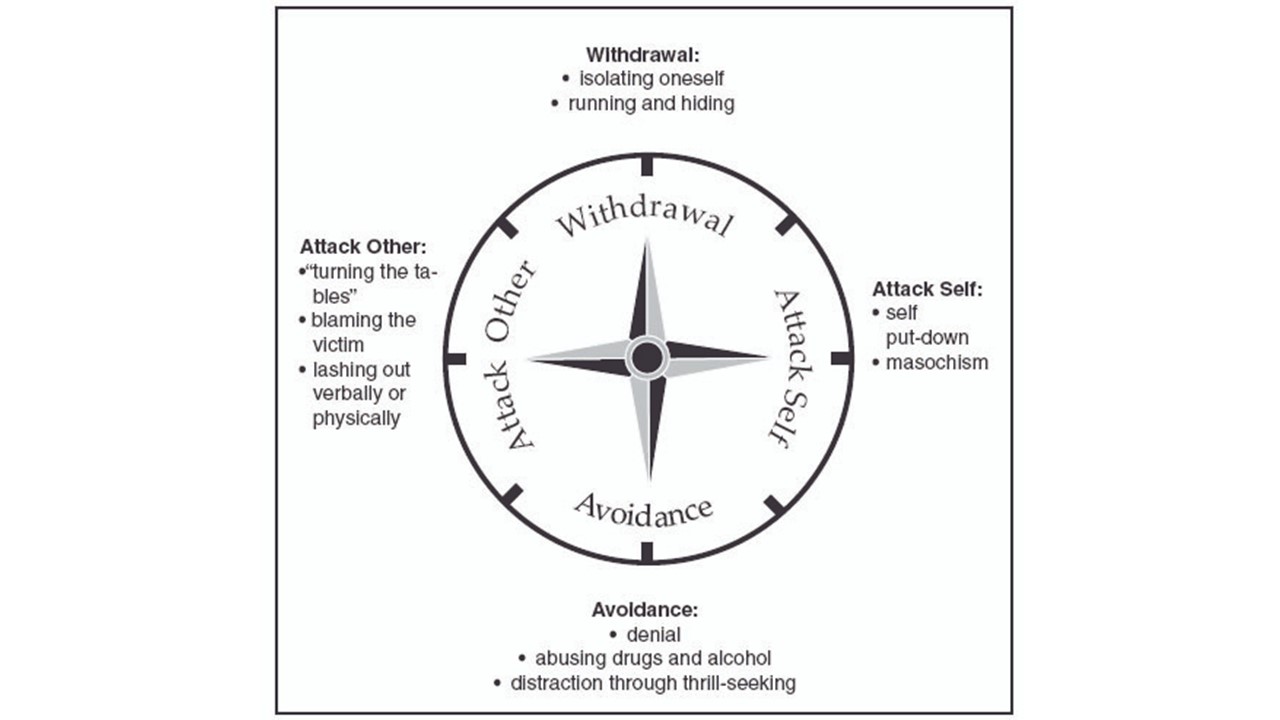

Psychiatrist Donald Nathanson explored this in his work on restorative practices, where shame often emerged as the central emotion being processed. He developed the concept of the “Compass of Shame,” observing the ways we tend to avoid processing shame through vulnerable engagement. When we resist facing shame, we tend to default to certain defences: attacking ourselves, attacking others, withdrawing, or avoiding. These defences often manifest as aggression, depression, isolation, and addiction.

My suggestion is to approach shame with curiosity. What is it trying to tell us? What is the signal it’s sending, and where is it leading us? This might feel challenging because, when we’re in the grip of shame, the instinct to escape or avoid it can be overwhelming. We may think, “How can I be curious about something that makes me want to run away?”

Yet, that is exactly what we must do—and what we must help others to do. Processing shame requires us to approach it through relationship and dialogue.

Relationship is always the key. It is through connection, dialogue, and accompaniment that we create spaces for vulnerability. In these spaces, individuals can experience what it feels like to be truly seen and loved. We need to cultivate these kinds of connections in our parishes, churches, and schools, particularly when addressing issues like pornography, which often involve this deep-rooted emotion of shame.

Shame is not the end of the story. Beneath it lies a true self, an inmost being within each of us. The internalized toxic shame that Sarah and so many others struggle with does not define them.

Our goal must be to facilitate corrective emotional experiences that can “update” shame memories, allowing people to release the core beliefs that hold them captive. This healing—this transformation—occurs through relationship and dialogue.

Returning to Sarah, I described the surface aspects of her addiction, her acting out, and her self-destructive behaviors. Each pole of the Compass of Shame was present in her life.

Through daily accompaniment and relationship, Sarah has experienced a corrective emotional journey—one in which she feels loved and cared for. This is a gradual, long-term process. Yes, she needs many forms of support: behavioral programs, possibly medication, and other interventions. But it’s these deep, underlying layers that most need to be unfolded and addressed in her life. We learned, for example, that she was exposed to pornography at a very young age. From about the age of seven, she had unrestricted access to increasingly harmful material.

Her early exposure left lasting impacts and trauma. Despite her efforts—she goes to confession regularly and has tried many ways to find healing—she carries a profound inner burden. This is why we must be willing to go deeper with people, beyond surface-level behaviors, to understand the roots of their pain.

Additionally, as a child, her parents placed her on multiple diets, perceiving her to be overweight. She was frequently weighed, measured, and scrutinized—a process that escalated her body image struggles and cultivated a deep sense of self-loathing. Through our daily accompaniment, she came to realize that this self-loathing was a key driver in her turn to pornography, which fueled her cycles of addiction.

So, how should we as a Church respond? For Sarah, her behavior carries a tragic logic; in her context, pornography became a means of coping with self-loathing at a young age. This brings us to the image of the Good Samaritan.

This image communicates to Sarah that her life was never meant to be this way. She was not meant to endure such harm; now, like the injured person on the roadside, she needs us as a Church to walk alongside her, offering a Good Samaritan’s accompaniment over a long period.

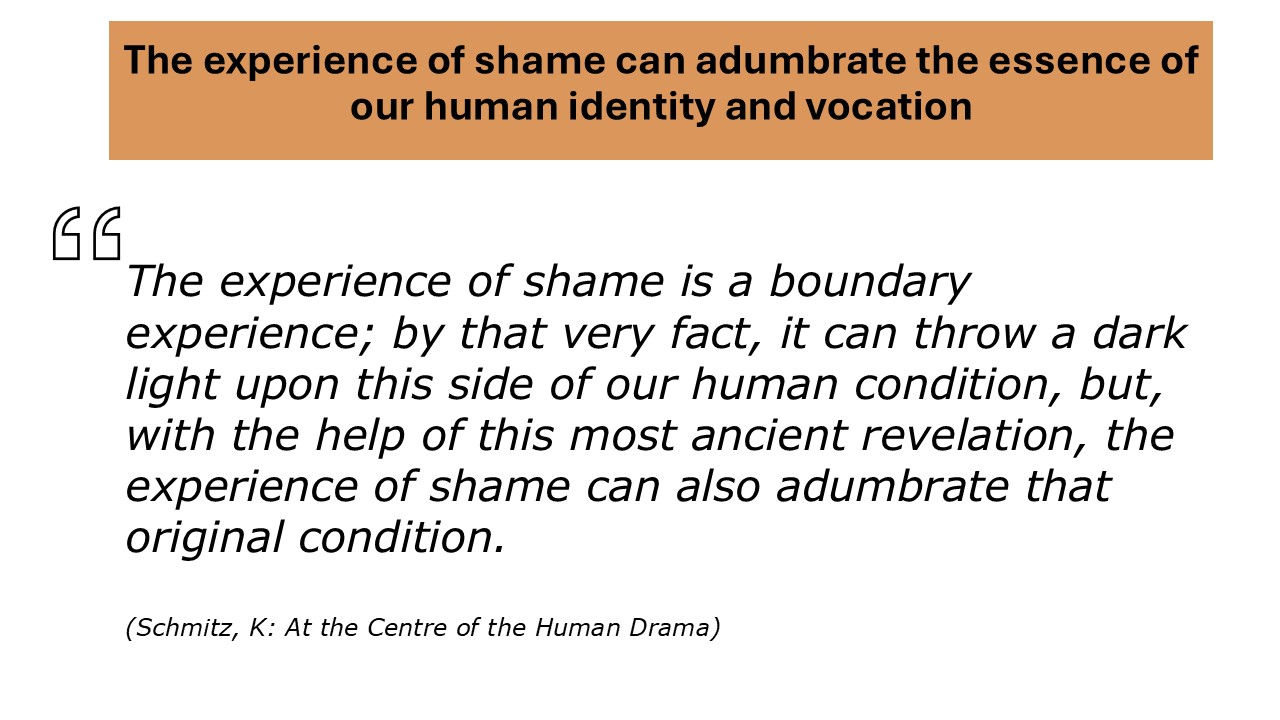

This form of accompaniment enables shame to be transformed. In this context, shame no longer serves as a toxic influence; instead, it can become a liminal, or boundary, experience—a reintegrative experience of shame.

Saint John Paul II speaks to this concept in his Theology of the Body, particularly when he reflects on the original experience of solitude. This solitude, according to him, leads to a discovery of self-consciousness, self-reflection, and personhood, paired with a capacity for self-determination. In Genesis, this “original nakedness” is described as carrying no shame. The biblical text profoundly reveals that our present state is continuous with a former state of innocence. Shame, in this sense, echoes or shadows our true identity, and it is through relationships that this truth can emerge.

As we accompany those suffering from pornography addiction, we must be willing to journey with them to deeper levels, allowing them to confront their internalized shame. Through this relational experience, they can begin to recognize that their shame, while profound, points to something greater—their true identity.

This shame, however deep, is not the end of the story. Instead, it reflects a shadow of their true identity as beloved children of God.

This is what Jesus did consistently—he encountered people. With the woman caught in adultery and others, he saw them fully and embraced them, giving them a glimpse of their true identity, an echo of who they were meant to be. This encounter is an encounter with our bodies, as shame itself is a deeply embodied experience.

As Saint John Paul II writes, “The body, in fact—and only the body—is capable of making visible the invisible, the spiritual and divine. It has been created to transfer into the visible reality of the world the mystery hidden from all eternity in God and thus to be a sign of it.” Walking with others allows them to process their shame and come to terms with the experience of their own bodies.

This is a profound journey, but one we can undertake with confidence because, in the context of a loving relationship, people can experience the other side of shame. This boundary, which feels so painful, holds the key to their true identity, which can only be revealed through relationship. This relational approach embodies the essence of Christ’s healing presence, bringing love, compassion, and peace to our inner conflicts and addressing the defences built around our shame.

As Pope Francis describes it, this process “holds in tension the experience of a dignified shame and a shame dignity, where one seeks a humble and lonely place but is also able to allow the Lord to raise him up for the good of the mission.”

Three main points from this talk:

Understanding Shame: Shame is a complex and often misunderstood emotion that differs from guilt. It’s an internalized feeling of inadequacy that can overwhelm individuals, manifesting in various destructive behaviors. Engaging with shame as a signal rather than a villain is essential for healing.

Relational Healing: Transformation of shame requires a relational approach. Through dialogue, companionship, and emotional support, individuals can process their shame and begin to disconfirm harmful beliefs about themselves. This corrective emotional experience is crucial in overcoming deep-seated trauma and addiction.

Faith and Identity: The church’s role is vital in accompanying those suffering from shame and addiction. By fostering environments of acceptance and love, individuals can reconnect with their true identity as beloved children of God. This transformative process reflects the essence of Christ’s healing presence and helps individuals move beyond their shame.